From the guidelines, as from January 2013: "People do not need to wait for permission to log your EarthCache. Requiring someone to wait is not supported by the EarthCache guidelines. People should send their logging task answers to you, then log your EarthCache. When you review their logging task answers, if there is a problem, you should contact them to resolve it. If there is no problem, then their log simply stands."

Mrs Macquarie's Chair - DP/EC52

S 33° 51.581 E 151° 13.351; Sydney Downtown, NSW

Mrs Macquaire's Chair, otherwise known as Lady Macquarie's Chair, provides one of the best vantage points in Sydney. The historic “chair” was carved out of a sandstone ledge for Governor Lachlan Macquarie's wife, Elizabeth, as she was known to visit the area and sit enjoying the panoramic views of the harbour.

Mrs Macquarie's Point, directly east of the Opera House on the eastern edge of the Royal Botanic Gardens, provides excellent views west across the harbour to the Bridge and the Mountains in the far distance. Looking north and east you can see Kirribilli House, Pinchgut Island and the Navy dockyards at Wooloomooloo. The views from Mrs Macquarie's Chair are still enjoyed today, over 150 years later, by hundreds of Sydney siders and tourists each day.

On top of all this iconic location is a perfect place to see, feel and learn about sandstone.

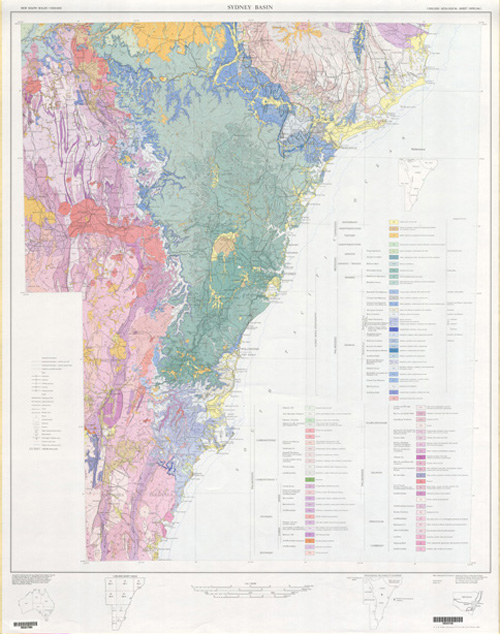

Sydney’s geology

Sydney is mostly Triassic rock, with a few more recent igneous dykes and the odd volcanic neck. The dominant geological member is the Hawkesbury sandstone, some 200 metres thick, with current bedding, shale lenses and fossil riverbeds dotted through it to make the cliffs more interesting.

On isolated ridges, a capping of Wianamatta shale makes richer soil, and below the sandstone, assorted shales, mudstones and other sedimentary layers go all the way down to the Permian coal measures, deep below Sydney.

At some time in the past, the whole Sydney area was worn d own to a flat plain, close to sea level. Then the land rose, or the sea fell, and the rivers and streams cut down into the rock. For the most part, the water flowed along a series of joints, planes of weakness in the rock which mainly run north and south. This flow produced a fern-leaf pattern of drainage that cut deeply between the tough sandstone which survived in ridges, high above the water, and in cliffs, where pieces of rock fell away, whenever a shale lens or a softer sandstone bed was eaten out, and a joint in the sandstone was undermined.

own to a flat plain, close to sea level. Then the land rose, or the sea fell, and the rivers and streams cut down into the rock. For the most part, the water flowed along a series of joints, planes of weakness in the rock which mainly run north and south. This flow produced a fern-leaf pattern of drainage that cut deeply between the tough sandstone which survived in ridges, high above the water, and in cliffs, where pieces of rock fell away, whenever a shale lens or a softer sandstone bed was eaten out, and a joint in the sandstone was undermined.

In recent times, the sea levels rose again, and the sea came flooding back, filling the river valleys to make what the geographers call a drowned river valley system. The Blue Mountains are the same sandstone, raised up in the past, except for a few ancient volcanic remnants like Mount Wilson, and Mount Tomah, where the Mount Tomah Gardens are located.

The city has been shaped by its geology. Nearly all of the rocks that you see exposed around Sydney will be sandstone. The sand that was to become this sandstone was laid down in the Triassic period, about two hundred million years ago, a time when plants were ferns, reptiles were becoming dinosaurs, and mammals were only just being thought about.

There are some remnants of more recent volcanoes around, but almost everything that you can see is good old-fashioned sedimentary rock, lying in almost horizontal layers. Not quite horizontal: the rocks around Sydney are shaped into a basin (or at least like half a basin) with the bottom of the basin somewhere near Fairfield, to Sydney's west.

The sandstone that defines Sydney was laid down almost 200 million years ago. The sand was washed from somewhere else, maybe out around Broken Hill, and laid down in a bed that is about 200 metres thick. Currents washed through it, leaching out most of the minerals and leaving a very poor rock that made an insipid soil. They washed out channels in some places, while in others, the currents formed sand banks that show a characteristic current bedding or cross-bedding that can often be seen in cuttings.

The sandstone that defines Sydney was laid down almost 200 million years ago. The sand was washed from somewhere else, maybe out around Broken Hill, and laid down in a bed that is about 200 metres thick. Currents washed through it, leaching out most of the minerals and leaving a very poor rock that made an insipid soil. They washed out channels in some places, while in others, the currents formed sand banks that show a characteristic current bedding or cross-bedding that can often be seen in cuttings.

Over time, the bed was bent somewhat, so that the Hawkesbury sandstone is now rather like a saucer that has been broken in half. The base of the sandstone is above sea level when you go north of Long Reef or somewhere south of Port Hacking, so that shales and mudstones begin to appear. You will actually see a few small shale lenses in the Hawkesbury sandstone, but these are rare.

At some time in the past, a monocline formed to the west of Sydney. If you don't know the term, the monocline is a sloping bend that raises the sandstone well above where you would expect to see it, and this is why the whole of the visible top of the Blue Mountains is made of sandstone.

The shaping of Sydney Harbour

Around Sydney, though, the whole area was ground down by erosion to a flat plain, but then either the sea level fell, or the land rose, and erosion could start again. Most large beds of rock have vertical planes of weakness running through them, and in the Hawkesbury sandstone, there are two sets at right angles, running more or less north-south and east-west.

Under erosive forces, the joints tended to take the water, and cut down faster, so when water began running off the newly-raised plateau, water found its way off through and along the joints, and created a fern-leaf pattern of gullies and valleys.

Then the sea level rose again, flooding Broken Bay, Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour), and Port Hacking, all of which show the characteristic pattern of drowned river valleys.

This has made for a disastrous transport situation: roads have to go up and down hills or over bridges, and tunnels are very hard to cut. Worse, when it comes to putting in railways, it is almost impossible to get reasonable gradients. As Sydney was settled, transport determined where people would build.

This is why Manly got its start, because people could get there by Manly ferry, but there was a different geological effect along the 'North Shore', where settlements spread along the ridge, catching the good soil that derived from a thin capping of Wianamatta shale, the bed that overlies the Hawkesbury sandstone. Because people were there, a train line started near Milson's Point, and worked its way to the far end, while in the inner west, it was tram lines that determined where developments would happen.

Later on, many of the gaps were filled in, but there are still many places where the shores were hard to access, so they were left fringed with bush, which is now able to catch fire in summer and carry fire to the houses above.

The other thing that shapes Sydney is the desire to get a water view. You haven't really arrived until you have a water view. As you travel around Sydney, you will see evidence of this wherever you go.

Claiming the EarthCache

Claiming the EarthCache

This is really easy to do once you are facing Mrs Macquarie’s Chair. Observe carefully and answer the following 5 questions and perform the additional task:

- Substitute for X: “X miles”; “XXX yards” and “XX Day of June XXXX”?

- What supports the overhang of sandstone to the left (as you face it) of Mrs Macquarie’s Chair?

- How many carved wide steps and how many carved narrow steps are there at the site? (Total number = 8; The laid steps curving on the right don’t count).

- Get up close to the sandstone and tell me whether the cross-bedding (the laminae) in the sandstone is mm-size or cm-size?

- What defines bedding in this sandstone?

(Optional)In addition, upload a picture of you or your team in front of or sitting on the chair just so that I can place a face to the name -;).

Send me the answers, with a clear identification of the EarthCache, via my GC profile and log your found. Enjoy the EarthCache.

Note: Platinum EarthCache level "ribbon" courtesy of Play mobil.

References:

- http://members.ozemail.com.au/~macinnis@ozemail.com.au/syd/environment.htm

- R. Brough Smyth (1873). First sketch of a geological map of Australia including Tasmania, F.G.S., F.L.S., Assoc. Inst. C.E.

- Bryan J.H., 1966, Sydney 1:250 000 Geological Sheet SI/56-05, 3rd edition, Geological Survey of New South Wales, Sydney.

The Podium:

Gold: geomatica Silver: Walenators / rudi63 Bronze: Deputy D0g

The most exciting way to learn about the Earth and its processes is to get into the outdoors and experience it first-hand. Visiting an Earthcache is a great outdoor activity the whole family can enjoy. An Earthcache is a special place that people can visit to learn about a unique geoscience feature or aspect of our Earth. Earthcaches include a set of educational notes and the details about where to find the location (latitude and longitude). Visitors to Earthcaches can see how our planet has been shaped by geological processes, how we manage the resources and how scientists gather evidence to learn about the Earth. To find out more click HERE.

The most exciting way to learn about the Earth and its processes is to get into the outdoors and experience it first-hand. Visiting an Earthcache is a great outdoor activity the whole family can enjoy. An Earthcache is a special place that people can visit to learn about a unique geoscience feature or aspect of our Earth. Earthcaches include a set of educational notes and the details about where to find the location (latitude and longitude). Visitors to Earthcaches can see how our planet has been shaped by geological processes, how we manage the resources and how scientists gather evidence to learn about the Earth. To find out more click HERE.