This guide is essentially a "geologic treasure hunt" where you

find features of geologic interest along the trails west of the

National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder,

Colorado. Using this guide, you will see many of the features that

geologists study and use to interpret the geologic history of the

Rocky Mountains. You will see various kinds of sedimentary rocks,

see how these rocks control landforms, see fossils associated with

these rocks, and observe changing environments over geologic time.

As you follow this tour, you will be walking through time across

older and older rocks.

© University Corporation for Atmospheric Research

Boulder is located at the junction of two major North American

geologic provinces: the Rocky Mountains on the west and the Great

Plains to the east. This is especially clear from Table/NCAR Mesa

as you look around you.

You will start at the NCAR parking lot. Broadway is the major

road through west Boulder. Turn west onto Table Mesa Drive and

follow Table Mesa Drive as it rises above the housing developments

and turns south (left) onto the top of Roberts /Table/NCAR Mesa

where NCAR is situated. This mesa is called Table Mountain on the

Eldorado Springs topographic quadrangle and Roberts Mesa at NCAR.

There is a 675 ft (206 m) rise in elevation from Broadway to the

NCAR parking lot. From the parking lot, walk west to where the

trail starts just north of the entrance to the NCAR building. The

tour is a hike of as much as 1.2 miles (1.9 km) one way (2.4 miles

total) and will probably take between 2 and 3 hours to complete.

You may do a portion of the tour if you wish and have a great hike

with exceptional mountain views.

The information given in this style of type gives directional

information from stop to stop.

Walk west along the north side of NCAR. You will see a big rock

with the words "Walter Roberts Nature Trail" near a kiosk

containing a map of the trails west of NCAR.

© University Corporation for Atmospheric Research

© University Corporation for Atmospheric Research

>

>

© University Corporation for Atmospheric Research

N 39° 58.709

W 105° 16.538

Stop 1 - The Boulder with the words "Walter Roberts

Nature Trail". This huge boulder has some very well exposed bedding

features. Walk around the boulder to the west facing side. You will

see sedimentary layers that form a large number of cross-beds

(where a flowing current of water deposits layers at an angle and

where layers intersect at different angles). These are trough

cross-bed sets deposited in rapidly flowing rivers. Trough beds

form when sinuous crested dunes move into scours that have been

scooped out in front of the dune (see diagram below). This boulder,

though transported, came to rest with the original top still

up.

Trough cross-bed sets. Diagram from Harms

and others, 1975

Can you tell the direction of the original river flow when the

sediment was deposited?

The composition of this boulder is arkosic, which means it is

composed of grains derived from granite. Arkoses are composed of

grains of quartz, feldspar and granite fragments. The quartz grains

are white to gray, glassy with no flat broken surfaces (since the

quartz has no cleavage planes). The feldspar grains are typically

pink, less glassy, and have flat surfaces along their cleavage

planes. Feldspars typically reflect sunlight ("flash") along their

cleavage surfaces. Particles of granite have interlocking quartz

and feldspar crystals. Also in the boulder are gray fragments of

metamorphic rock (quartzite).

This boulder is stained red due to the weathering of iron-rich

silicate minerals. Biotite mica and amphibole have weathered into

red iron oxide minerals (mainly hematite, Fe2O 3). The darker lines

represent laminations and thin beds of finer-grained sediment. In

some places, the iron oxide has been leached away forming white

"dots" on the rock surface.

Continue walking along the path to where the trail forks at the

Mesa Trail sign. Stop, read the following discussion and look

around, then take the left fork of the trail.

You are walking on Roberts/Table/NCAR Mesa that is capped by

gravel containing giant boulders derived from the Fountain

Formation that outcrops in the Flatirons to the west. The elevation

of this boulder gravel, the degree of weathering, and relationship

to other gravels in the region suggest that it was deposited about

2 million years ago (during the late Pliocene).

The view to the left (toward the southeast) is of the valley of

Bear Creek that is cut into the Pierre Shale. The Pierre Shale is

about 8000 feet (2445 m) thick and floors Boulder Valley. You can

see the top of the Pierre Shale on the far side of South Boulder

Creek near the town of Marshall (see photo below). On the south

side of Bear Creek, you can see the top of another mesa that slopes

gently eastward. Like NCAR mesa (on which you are standing), the

mesa across Bear Creek is also capped by gravel derived from the

Fountain Formation eroded from the Flatirons. This coarse debris

overlies steeply inclined rocks of the Pierre Shale.

Continue walking on the left fork of the trail along the mesa

edge until you come to the "Fire and Drought" sign.

N 39° 58.642

W 105° 16.648

Stop 2 - View at the "Fire and Drought" sign. On the skyline

to the southwest, locate Bear Peak and the Devil's Thumb (diagram

below).

Continue walking along the path until you reach just beyond the

"Flooding and Erosion" sign.

Along the left side of the trail are blocks of Fountain arkose

with large "birdbath" pits on their tops. Such pits start to form

on smooth boulder surfaces and continue to grow because water is

ponding on top of the boulder. Here a combination of chemical and

physical weathering enlarges the pit. They form on boulders or rock

outcrops that have been exposed for a long time to the

elements.

Continue walking along the trail until you come to the second

map kiosk. Follow the right path to the "Mountain Waves" sign.

N 39° 58.646

W 105° 16.721

Stop 3 - View from the "Mountain Waves" sign. Look beyond

the sign toward the northwest and you can see the Flatirons

supported by the Fountain Formation and a light-colored quarry cut

into the Lyons Sandstone, the formation that is stratigraphically

on top of the Fountain Formation. (see below).

Figure 3. View to the northwest of the flatirons and the

quarry in the Lyons Sandstone

Figure 3. View to the northwest of the flatirons and the

quarry in the Lyons Sandstone

Walk back to the map kiosk and take the path to the Mesa Trail.

Walk down the slope past the first switchback (turning to the left)

and stop at the second switchback turning to the right.

N 39° 58.628

W 105° 16.710

Stop 4 - Second switchback below Table/NCAR Mesa. This

switchback is near the contact between the boulder gravels that cap

Table/NCAR Mesa and the Upper Cretaceous (about 81-68 million years

old) rocks below. During this time, Colorado was covered by the

Western Interior Seaway that extended from the Gulf of Mexico to

the Arctic (see diagram).

The gravels are resting on a surface that is gently inclined to

the east. However, the Cretaceous rocks have been tilted 80° to the

east. You are also standing near the contact between the limestone

(chalk) of the Niobrara Formation and the black shales of the

Pierre Shale. The Niobrara limestones extend to the west from this

point, the Pierre Shale extends to the east. Below the switchback

you can see a light-gray ridge supported by limestone beds of the

upper Niobrara Formation (diagram below). There is a gap in time

(angular unconformity) between the tilted Cretaceous rocks (+80

million) and the much younger gravels (2 million) on top of the

mesa. Think about what has happened to cause this gap in time

between these units. This will become clearer farther along the

trail.

Continue walking down the trail into the juniper grove to where

the trail bends to the right.

N 39° 58.628

W 105° 16.742

Stop 5 _ Limestone beds below the giant block of arkose. In

the junipers and below the giant block of Fountain arkose (on the

north side of the trail), the trail crosses some light gray

limestone ledges. These limestone ledges are in the lower Niobrara

Formation (Smoky Hills Member). Some of the limestone ledges

contain shells and shell fragments of large marine clams called

inoceramids. The shells are darker gray than the limestones and

have prismatic structure on the broken edges of the shell

fragments. _ Prismatic _ means that the shell is composed of small

needles (prisms) of calcite oriented perpendicular to the outer and

inner surfaces of the shell. The clam shells changed in form and

size through time (diagram below) from smaller wing-shaped shells

(Mytiloides spp.) to smaller bowl-shaped shells (Cremnoceramus

spp.) to huge platter-like shells (Platyceramus spp.). The

inoceramids in this limestone had bowl-shaped shells that are

crescent-shaped in cross section. Figure 6 below shows the location

of one of the most fossiliferous limestone layers.

Using Figure 5 and observing the form and stratigraphic position

of these clams, which member of the Niobrara Formation do you think

that you standing on? Notice also that the limestone layers have

numerous vertical cracks, called joints.

Continue down the path to the valley between Table/NCAR Mesa and

the next ridge (Dakota hogback). Stop by the wooden fence.

N 39° 58.653

W 105° 16.757

Stop 6 _ The valley between Table/NCAR Mesa and the Dakota

hogback. Between the resistant ridges capped by boulder gravels of

Table/NCAR Mesa and the sandstones of the hogback forming the ridge

to the west (sandstones of the Dakota Group) is a valley cut into

the soft shale beds of the Benton Formation. You can see fragments

of the dark gray shales in the cut at the base of the wooden fence.

Mudrocks, such as shale, tend to be easily eroded. You may also

find yellow, clay-rich mudrocks in the cuts below the fence. These

are layers of altered volcanic ashes called bentonites. The

volcanic glass of the ash has been altered into swelling clays that

can expand as much as 12 times its dry volume when the bentonite

becomes wet. Such swelling clays play havoc on building foundations

that are built on bentonites.

Continue walking on the trail, climbing up the Dakota hogback.

Walk to the second switchback.

N 39° 58.678

W 105° 16.839

Stop 7 - Second switchback on the Dakota hogback. You are

now standing near the top of the Dakota Group. The sandstone beds

of the Dakota have been uplifted from near sea level to an

elevation of 6200 feet and tilted from horizontal to an angle of

nearly 60°. Geologists describe these tilted beds by strike and

dip. Strike is the line of intersection between a horizontal plane

and an inclined plane (the inclined rock layer). Dip is the maximum

angle of inclination between the horizontal plane and the inclined

rock layer.

Dip is measured perpendicular to the strike line. If you dribble

water onto the sandstone bed next to the trail, the dip direction

is the direction of the flowing water as it runs down the rock

surface. Here the strike is N 14 W (14° northwest of true north)

with a dip of 58E (an inclination of 58° to the east). In contrast,

the strike and dip of the Cretaceous rocks near Stop 4 is N20W and

80E. As you climb up the trail you will be paralleling the strike

of several inclined sandstone beds.

Continue on to the top of the ridge.

N 39° 58.648

W 105° 16.884

Stop 8 _ Top of the Dakota hogback. Across the trail from

the large green water tank on the top of the ridge is a series of

sandstone beds that have been tilted. Examine the internal layering

on the edges of these beds. You will see some well-exposed planar

cross-bed sets. You will also see horizontal bedding in many of the

other sandstone layers.

Compare these cross-bed sets and the trough cross-bed sets at Stop

1. These represent a very different environment of deposition from

the arkose boulders of the Fountain Formation on Table/NCAR Mesa.

Here we find shallow marine and beach deposits. These are the near

shore deposits along the Western Interior Seaway (see diagram).

Walk around the green water tank to the opposite side. Look for

examples of cross-beds and ripple marks on the sandstone. Irregular

squiggles in the surface of the sandstone are trace fossils that

are the burrows made by some kind of marine organism.

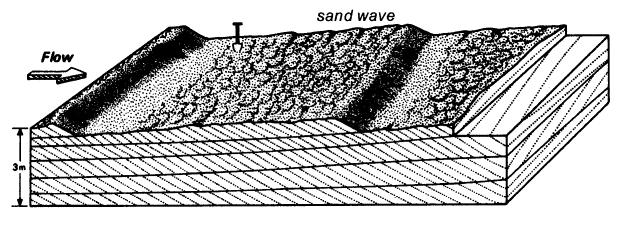

Origin of planar cross-bed sets, or cross-bed sets that are

bounded by flat (planar) surfaces. Notice that the dunes are

straight-crested sand waves that climb up the back of the previous

dune. Diagram from Harms et al. 1975, Fig. 3-2. Continue to walk

west down the trail, across the sandstone ledges, through a slight

dip to a smaller ridge where the trail jogs to the right. This

small ridge is next to a ponderosa pine tree with multiple trunks

on the left side of the trail.

N 39° 58.660

W 105° 16.933

Stop 9 _ Sandstone beds of the lower Dakota Group. The

sandstones in this low ridge are in the lower part of the Dakota

Group (a group consists of several formations). These lower

sandstone beds are separated from the upper Dakota sandstone beds

by a sequence of shale beds that erode into a gully.

Continue down the trail to the fork in the trail. Take the left

fork. Walk out to the pine-covered ridge where the trail curves

strongly to the right.

N 39° 58.645

W 105° 16.986

Stop 10 _ Pine covered ridge. This ridge is in the lower

beds of the upper Jurassic Morrison Formation that is composed

mostly of multiple-colored mudstone beds. There are also very thick

lens-shaped (lenticular) sandstone beds and thin limestone beds.

You can see these rock types along the trail and in the outcrops in

the gully to the east (diagram below - Figure 7). The white

sandstone ledge pinches out (disappears) both up and down the hill

and was originally deposited in a stream channel. Dinosaur bones

have been found in these channel sandstone beds, but people have

removed the bones over the years.

Walk about 30 paces down the trail from the center of the curve

on the ridge. You will cross into red soil and end on a series of

red sandstone beds.

N 39° 58.649

W 105° 17.005

Stop 11 _ Red beds of the Lykins Formation. The Lykins

Formation (Permo-Triassic) is composed of a series of mudstone,

shale and sandstone beds that are all brilliant red. The Lykins

mudrocks are not resistant to weathering, so the Lykins is

typically exposed in a long, linear valley between the Dakota

hogback and the Lyons Sandstone, which forms part of the Flatirons.

The sandstone beds at this stop are surrounded by darker red

(maroon) shale beds, and both strike N15W with a dip of 59E.

Continue walking down the trail to the junction with the Mesa

Trail. At the junction you will continue to walk west on the

Mallory Cave Trail.

Look west at this trail junction and you will see on the west side

of the valley a series of white blocks of rock that support a small

ridge (see Figure 8). These blocks are composed of dolomitic

(calcium magnesium carbonate) limestone of the Forelle Limestone

Member of the Lykins Formation.

Since you will be staying on the trail, you will not be walking up

to this ridge. However, you can walk to a block fallen from the

Forelle that is along the trail. See Figure 7 to see where this

block is located, and walk to this block. Be careful of the poison

ivy that grows near the block and along the trail.

N 39° 58.677

W 105° 17.071

Stop 12 _ A block from the Forelle Limestone Member. This

block is the first gray rock on the right that is covered with

yellow and orange lichens. Notice on the side of the block there

are mostly horizontal laminations with some curved laminations. The

horizontal laminations were formed by algal (bacterial) mats and

the curved laminations were formed as stromatolites.

Cross-section through a

stromatolite

Find the curved laminations on the side of the block.

Continue walking up the trail through the pines along the Mallory

Cave Trail. Walk through the pines into an open area and to the

place where the trail turns left across a dry gully. Walk a little

farther to the sandstone ledges.

N 39° 58.569

W 105° 17.120

Stop 13 _ Sandstones near the top of the Lyons Sandstone.

Pick up a small block of sandstone, preferably with a freshly

broken side. Looking closely at the block (preferably with a 10X

hand lens), you will see that it is composed almost exclusively of

fine to very fine quartz sand grains that are all about the same

size ( it is well-sorted). Notice that the sandstone _ sparkles _

on freshly broken surfaces. This is because the Lyons is a quartz

sandstone cemented with quartz cement. You may also see thin layers

(laminations) composed of black minerals. These minerals are

iron-rich and includes the black mineral magnetite (Fe3O4).

Look back along the trail toward the north (across the gully).

You can see a cone-shaped pile of Lyons sandstone blocks (rubble)

that cover the slope. This rubble is called talus, and makes up

what is called a talus cone.

Continue along the trail up the hill. You will cross some small

ledges of Lyons Sandstone in the trail and finally come to a much

larger outcrop on the right side of the trail. This outcrop shows a

large, smooth surface of a sandstone bed (Figure 9) that is below a

pine tree. Stop at the base of this outcrop.

N 39° 58.493

W 105° 17.162

Stop 14 _ Sandstones near the bottom of the Lyons Sandstone.

Look at the lower right of this outcrop. You will see some faint

linear features that trend at a slight angle downward from the left

to the right (Figure 9). These are some very low-crested ripples.

Such low-crested ripples and the well-sorted quartz sands of the

Lyons indicate (in part) that the Lyons was deposited as sand dunes

by wind.

You might think that the flat surfaces of the Lyons sandstone beds

are excellent places to determine strike and dip. These surfaces

are easy to measure, but there is a huge variation in the

measurements, especially in the strike values. However,

measurements of strike and dip of beds in the nearby Fountain

Formation are consistently about N14W with a dip of 50E. These

surfaces are large-scale cross-beds and this produces the

variations in the attitudes in the Lyons sandstone beds. There are

so many of these cross-beds in the Lyons Sandstone that it is

nearly impossible to get a strike and dip measurement that reflects

only the tilting by the uplift of the mountains.

Look carefully at the rock surface and you will see raised squiggly

tubes on the surface. These are trace fossils. They were probably

some kind of burrowing animal that lived in the sand on the

dune.

Continue walking up the trail. Soon you will see conglomerate

(sand and pebble)beds of the Fountain Formation in the trail. Walk

to the 1st switchback (toward the right) that is near two gigantic

blocks of Fountain arkose on the left side of the trail. Walk down

below the trail and between the two blocks. Look at the edge of the

block on the left side as you walk downhill.

N 39° 58.479

W 105° 17.190

Stop 15 _ Gigantic blocks of the Fountain arkose. These

blocks have tumbled down from the Fountain Formation flatirons up

on the side of the mountain. The lower block is resting on its

side, so it looks like the bedding is vertical. Note that the

layering in this block includes horizontal beds, scours, and trough

cross-beds.

You are now approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) from the trailhead.

Continue to walk up the trail past two rock monoliths composed

of Fountain arkose. The trail goes between the two monoliths. Two

kinds of sedimentary rock(coarse and fine-grained) and two kinds of

bedding (cross and horizontal) occur in these outcrops. The bedding

reflects the river origin of these rocks. Walk just beyond the

monoliths and enter a small clearing. Continue walking up the trail

until you reach a post showing the entrance to the Dinosaur Rock

Climbing Area at the sharp turn to the right of the Mallory Cave

Trail.

N 39° 58.421

W 105° 17.226

Stop 16 _ Base of the Flatirons -- Dinosaur Rock. The

flatirons here are Permian, (about 300 million years old) Fountain

Formation. The rocks in this flatiron are all arkosic, and include

beds of conglomerates and maroon sandstones. They were formed in

rivers draining the Ancestral Rocky Mountains. These rocks strike

at N14W and dip 50E and they were tilted during the uplift of the

present Rocky Mountains about 64 million years ago.

This is the last stop of the tour. You can return back to the NCAR

trailhead, 1.2 mi (1.9 km) away, or you can take the right fork up

toward Mallory Cave. Not far beyond this post, the trail becomes

very steep with many switchbacks and is somewhat hard to

distinguish in some places. The final climb to the cave ( that

requires some simple rock climbing) is closed between April 1 and

October 1 because the cave is a nesting site for bats. However,

there are some spectacular views of Boulder Valley from the trail.

You can also continue along the Mesa Trail to the south. Bear

Canyon Trail will take you up along Bear Creek between the

Flatirons to the contact with the 1.7 billion year old Boulder

Creek Granite.

To log this EarthCache: To log this Earthcache, please send a

photograph of your self at any of the stops except number 1. Also,

send me the answer to any of the posed questions (let me know which

stop). Please also include in your log the number of people who

visited the sites with you.

References Cited Harms, J.C., Southard, J.B.,

Spearing, D.R., and Walker, R.G., 1975, Depositional environments

as interpreted from primary sedimentary structures and

stratification sequences: SEPM Short Course no. 2, 161 p.