Hier scheint das Sprichwort

"Alle Wege führen nach Rom" nicht nur metaphorisch zu gelten. Wir beschäftigen uns hier mit den geologischen Spuren der alten Römerstraßen und entdecke die Geschichte, die hinter jedem Stein verborgen liegt.

Das Streckennetz der Antiken Römerstraßen umfasste insgesamt 80.000 bis 100.000 Kilometer in ganz Europa. Der erste Abschnitt des Netzes wurde 312 v. Chr. als Teil der "Via Appia" fertiggestellt.

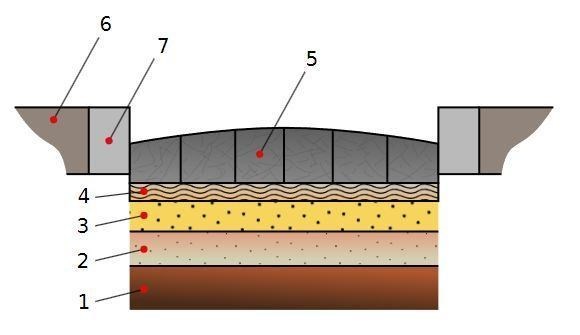

Für eine Römerstraße war immer Aushub bis über einen Meter in die Tiefe nötig, um den Grund (Nr. 1) zu sichern. Danach wurden mit groben Steinen (Statumen Nr.2), dann mit Kies (Rudus und Nucleus Nr. 3) und darauf mit Sand immer feiner werdende Schichten (Nr. 4) aufgebracht, bis die Fahrbahndecke mit Pflastersteinen (Nr 5.) auf eine vorgegebene Breite ausgeführt wurde. Randsteine (Nr. 7) formten Rinnen in die Konstruktion. Am Beispielfoto aus Pompeji ist schön zu erkennen, dass die Randsteine bzw. Fußwege höher gelegt wurden, damit das Wasser über die Fahrbahn abläuft.

Von Via_Munita.png: Smith, William, William Wayte, and G. E. Marindin - Diese Datei wurde von diesem Werk abgeleitet: Via Munita.png:, CC BY-SA 3.0, original

Von Via_Munita.png: Smith, William, William Wayte, and G. E. Marindin - Diese Datei wurde von diesem Werk abgeleitet: Via Munita.png:, CC BY-SA 3.0, original

Pflastersteine aus Leuzitit

Viele sind der Meinung, dass die oberste und für uns sichtbare Schicht der römischen Straßen (Nr. 5) aus Basalt gefertigt wurde, doch das ist ein Irrglaube – es handelt sich hierbei um weltweit gesehen sehr seltene Leuzitit. Leuzitit und Basalt sind sich sehr ähnlich: Beide Gesteine entstanden durch die Aufschmelzung des Erdmantels. Dünnflüssiges Magma, das bei Temperaturen zwischen 900 °C und 1200 °C aus dem Erdmantel austritt, erkaltet an der Erdoberfläche oder im Ozean relativ schnell zu Leuzititlava bzw. Basaltlava. Diese schnelle Abkühlung führte dazu, dass das Gestein größtenteils aus einer feinkörnigen Grundmasse besteht.

Betrachtet man sowohl die Festländer als auch den Grund der Meere, ist Basalt das Gestein mit der größten Verbreitung. Nahezu alle tiefen Ozeanböden bestehen aus Basalt, der dort nur von einer mehr oder minder mächtigen Decke jüngerer Sedimente bedeckt wird. Im Gegensatz dazu ist Leuzitit eine relativ seltene Gesteinsart weltweit, er ist hauptsächlich nur hier im Mittelmeerraum zu finden.

Was sind die Unterschiede von Leuzitit und Basalt?

Um das zu beantworten ist es wichtig zu verstehen, wie Basalt aufgebaut ist.

Man kann sich Basalt wie ein Puzzle vorstellen, in dem die Puzzleteile Silikate sind. Silikate bestehen aus Silizium, das sich mit Sauerstoff verbindet. Silizium ist das zweithäufigste Element in der Erdkruste nach Sauerstoff.

Diese Silikat-Teile bilden Tetraeder, das sind dreieckige Strukturen. In diesen Strukturen gibt es freie Verbindungen, die sich mit Metall (wie Eisen und Magnesium) oder anderen Elementen (wie Calcium, Natrium und Kalium) verbinden. Das Ganze nennt man Silikatkristalle.

In Basalt gibt es zwei Haupttypen von Silikaten: Pyroxene und Feldspäte. Pyroxene enthalten Kalzium, Eisen und Magnesium, während Feldspäte Kalzium, Natrium und Kalium enthalten.

Die Menge an Silizium, die im Magma verfügbar ist, beeinflusst, welche Mineralien entstehen und welcher Gesteinstyp entsteht. Basalte entstehen, wenn es genug, aber nicht zu viel Silizium gibt. In den Gesteinen der Pflastersteine ist viel Kalium, aber weniger Silizium als in normalen Basalten. Die Mineralien in den Pflastersteinen, wie Olivine, haben wenig Silizium. Kaliumhaltiger Feldspat kann sich nicht bilden, weil dafür mehr Silizium nötig wäre. Stattdessen entsteht ein Mineral namens Leuzit.

Leuzit ist ein weißliches Mineral mit rundem Aussehen, das im dunklen Gestein typische helle Kugeln bildet, die oft mit bloßem Auge sichtbar sind. Das Gestein, welches Leuzit beinhaltet wird Leuzitit genannt. Es ist nicht korrekt, es Basalt zu nennen, da basaltisches Magma mehr Kieselsäure enthält und in der Lage wäre, Kaliumfeldspat zu bilden. Wenn jedoch viel Silizium vorhanden ist, kristallisiert der verbleibende Teil nach der Bildung aller Silikate, die es bilden kann, in Form von Quarz, also einfachem Siliziumoxid, wie es beispielsweise in Graniten vorkommt.

Zusammengefasst bestehen die Pflastersteine also aus einem Vulkangestein, das wir Leuzitit nennen, weil es reich an Leuzit ist, dem Mineral, das im Vergleich zum Kaliumfeldspat, der sich normalerweise in einem Kaliumbasalt bilden würde, an Kieselsäure „untersättigt“ ist.

Mineral Leuzit © pasqualerobustini.com

Der in Latium für den Straßenbau verwendete Leuzitit wurde vom nahegelegenen, nicht mehr aktiven „Vulcano Laziale“, also den heutigen Albaner Bergen, abgebaut. Es ist das wohl größte Leuzititvorkommen der Welt.

Der Earthcache:

Um diesen Earthcache zu lösen, beantworte folgende Fragen und sende mir die Antworten per

Messenger zu. Nach dem Zusenden der Antworten kann gleich geloggt werden. Bei Unklarheiten oder falschen Antworten werde ich mich bei dir melden.

1.) Beschreibe mit eigenen Worten, wie Leuzitit entstanden ist.

2.) Beschreibe mir die Leuzitit-Steine: welche Farbe und Oberfläche haben sie?

3.) Schau dir den Leuzitit im Detail an, kannst du das Mineral Leuzit im Stein erkennen? Beschreibe das Mineral in Aussehen, Größe und Häufigkeit.

4.) Du solltest auch kleine Luftblaseneinschlüsse im Gestein finden. Woher könnten sie deiner Meinung nach kommen?

5.) Kannst du Einschlüsse von Fremdgestein finden? Wie groß ist der größte Einschluss den du findest? Wie sind diese in den Leuzitit gekommen?

6.) Mache ein Foto von dir oder einem persönlichen Gegenstand auf der antiken Römerstraße und lade es zu deinem Logeintrag hoch.

Quellen:

Photo: RauGeo

cross-section: wikipedia.org

Text: wikipedia.org / steinrein.com / pasqualerobustini.com